The long way to the 4th directive

The challenges to reduce the risk of money laundering and terrorism financing activities have recently been in the focus of the competent authorities, especially in Europe and the United States: the lack of control mechanisms and insufficient risk assessment of customers and transactions have led to considerable fines for several internationally operating financial institutions.

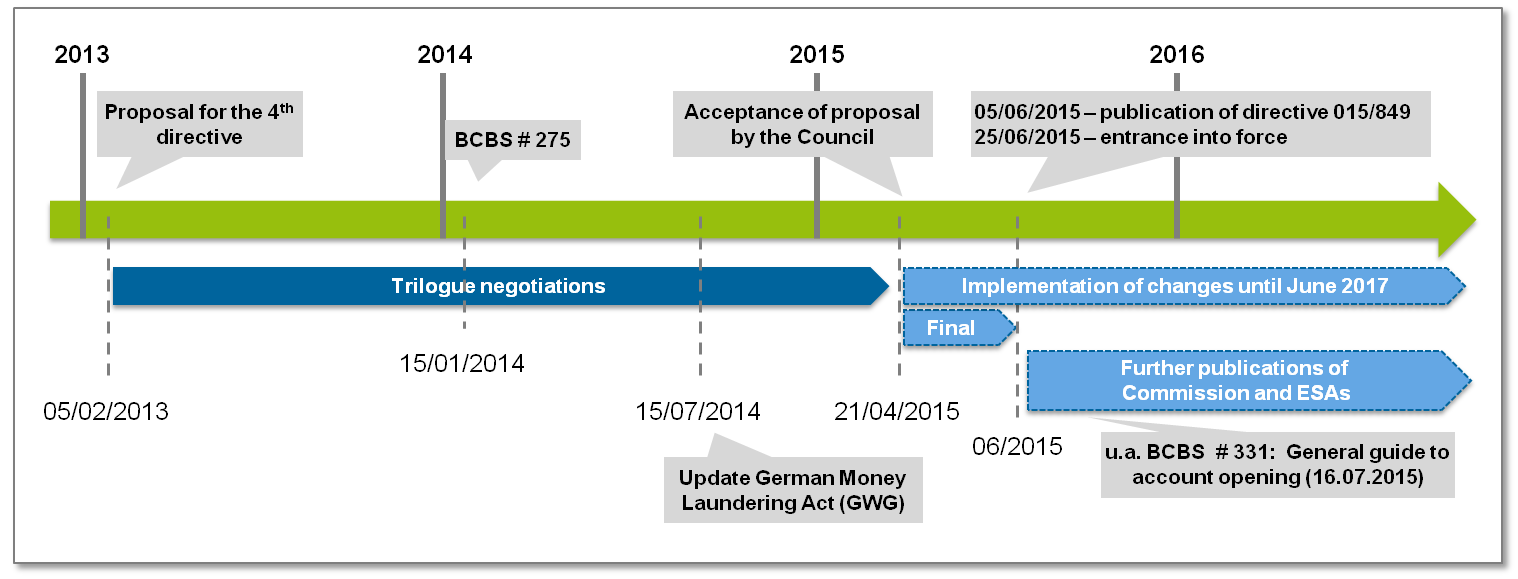

The risk associated with money laundering and terrorism financing has also been identified by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which revised its recommendations in 2012. Shortly after the publication, in February 2013, the Commission presented its first draft of a new directive; however, the finalization of the legislation process took more than two years and required trilogue negotiations between the Commission, Council and Parliament. During the consultation process, the Basel Committee on banking supervision also published a paper in 2014 [1], which already incorporated the revised FATF recommendations and influenced the consultation progress.

The new directive does not only take the obliged entities up on their promise

The 4th directive will require the obliged entities to change existing procedures and at the same time establish and define new processes. Furthermore, the directive integrates the European Supervisory Authorities (“ESAs”)[2]

into the legislative procedure and hereby authorizes them to develop a set of proposals for guidelines and standards.

A key element of the strategies to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing is the risk-based approach, which requires the assessment of risks at all levels: according to article 6 of the 4th directive, risk assessment shall be conducted on European level by the Commission until June 2017. The result shall be the basis for national risk assessments and “shall make recommendations to Member States on the measures suitable for addressing the identified risks” and further be subject to a regular review. Furthermore, ESAs are required to frequently issue their opinion “on the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing affecting the Union’s financial sector”.

According to article 7 of the 4th directive, Member States are required to “take appropriate steps to identify, assess, understand and mitigate the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing affecting it, as well as any data protection concerns”. This assessment shall be kept up to date and shall be made available to the Commission and ESAs.

The objective of this comprehensive risk-based approach by the bodies shall mitigate the risk of money laundering and terrorist financing throughout the European Union.

Additionally, article 30 of the 4th directive requires the Member States to establish a central register in each Member State which captures information on corporate and other legal entities within their territory holding “adequate, accurate and current information on their beneficial ownership, including the details of the beneficial interests held”. This central register is meant to be accessible by the financial intelligence units (FIU), obliged entities as they require this information for customer due diligence purposes as well as “any person or organization that can demonstrate a legitimate interest”. These national registers are intended to be harmonized and interconnected on a European level in the long run.

The ESAs will not only have a key role in the risk assessment process, but will also be required to develop standards, e.g. guidelines on the application of simplified obligations (article 17) or enhanced obligations (article 18) in the customer due diligence and various regulatory technical standards.[3] An example includes the specification of the requirements where a third country’s law does not permit the implementation of certain measures according to the 4th directive (article 45). This demonstrates the increasing impact of the ESAs into the legislative process, which could have been observed already during the implementation of the CRR/ CRD IV package. Hereby, the EBA has been asked to develop a high amount of guidelines and standards, which is still ongoing.

Further to those overarching changes in the treatment of money laundering and terrorist financing, obliged entities will be required to incorporate the new directive into their business.

The main issues for obliged entities can be summarized by risk assessment, customer due diligence and relevant thresholds.

Risk assessment

Article 8 (1) requires Member States “that obliged entities take appropriate steps to identify and assess the risks” by “taking into account risk factors including those relating to their customers, countries or geographic areas, products, services, transactions or delivery channels.” As this risk assessment regime not only applies on obliged entity level but also on European and Member State level, it can be seen as a key element of the new approach of the regulator.

However, the development of a risk assessment report will not be sufficient. Obliged entities have to ensure, that every single transaction will be analyzed according to its specific risk characteristics. Therefore, obliged entities will have to develop strategies, processes and control mechanisms to not only ensure that the transactions are appropriately assessed but also that they are appropriate to capture all potential risks of a transaction. This also requires a high level or awareness of the employees, as they have to apply this risk-based approach in their daily work.

Due Diligence

The concept of a customer due diligence (“know-your-customer – KYC”) is not a new concept, however the 4th directive will have a major impact on the obliged entities. In addition to an update of the thresholds for specific transactions which lead to general customer due diligence requirements, the 4th directive enhances the terminology of “politically exposed persons (PEP)”.

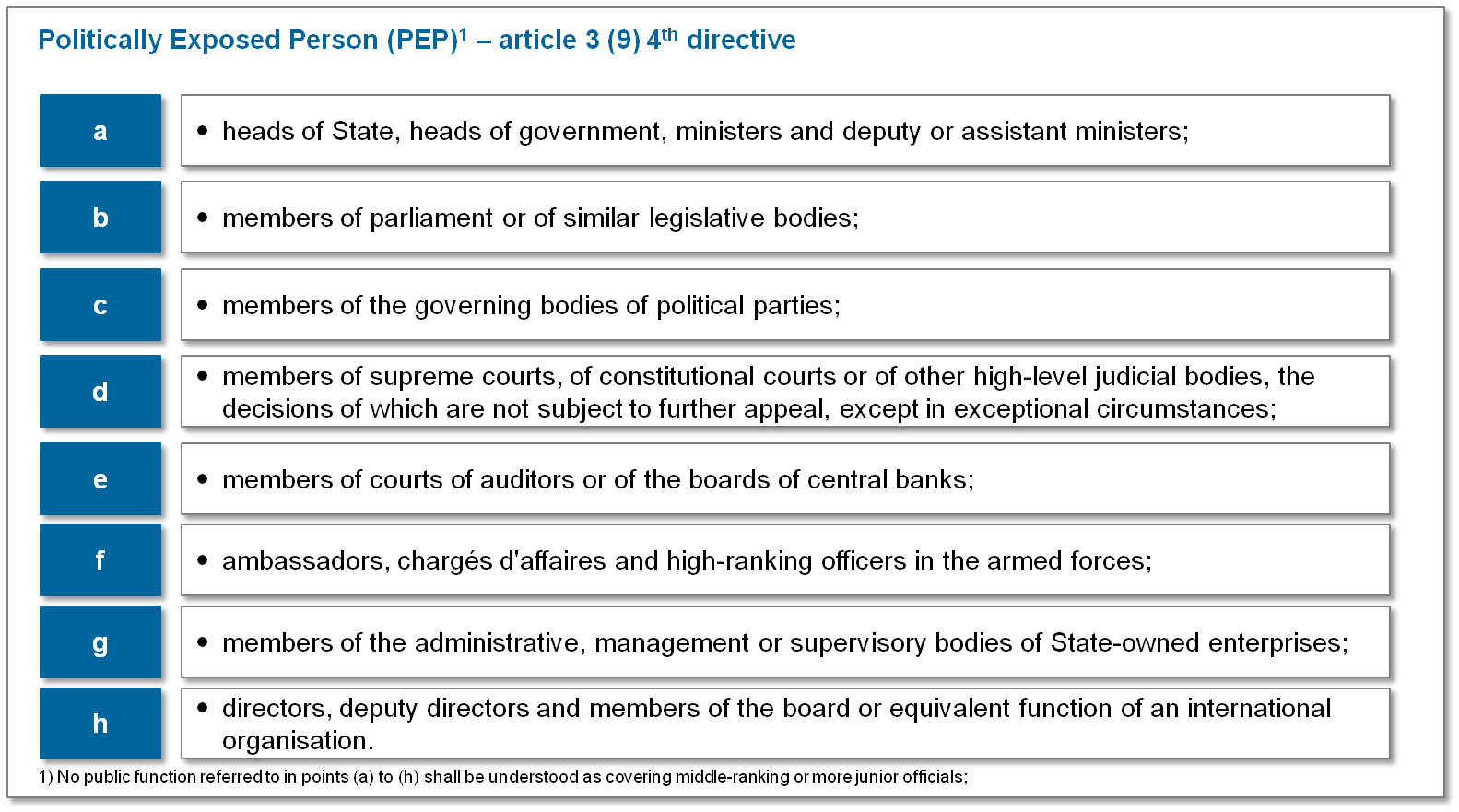

Within the 3rd directive, this term has been defined in article 3 (8) as “natural persons who are or have been entrusted with prominent public functions and immediate family members, or persons known to be close associates, of such persons.” As this concept has been too vague and as there is no central register available which includes an exhaustive list of potential PEP, the 4th directive concretizes the definition by naming positions. The term is defined as “a natural person who is or who has been entrusted with prominent public functions” and is accompanied by a list of functions this natural person shall have.

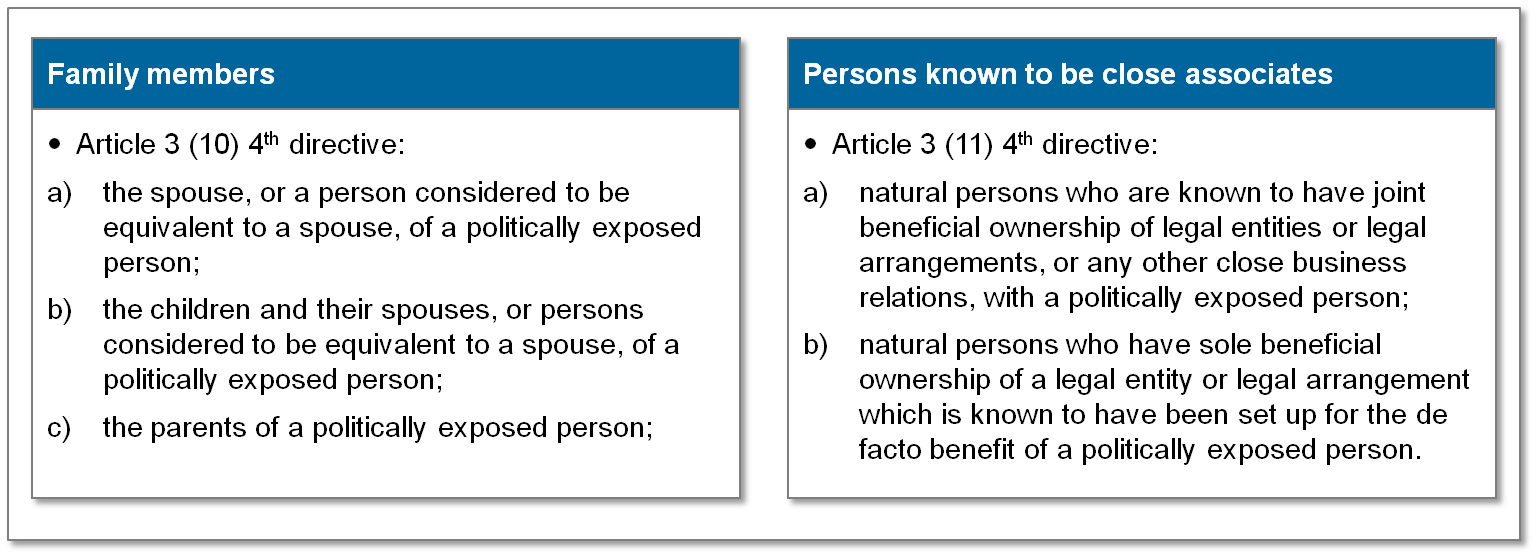

The consequences for transactions with PEP are set in article 20 and 21 of the directive. It requires obliged entities to establish a risk management system to identify potential PEP and to take specific measures when entering into a business relationship with PEP, including senior management approval, identification of source of wealth as well as ongoing monitoring of the relationship. These specific obligations also apply to “family members or persons known to be close associates of PEP” (article 23). Also, other than in the 3rd directive, those two terms are concretized in the 4th directive.

Obliged entities should therefore review their existing strategies and procedures to identify PEP, their family members and persons known to be close associates. This should not only apply for new customer relationships, instead it is recommended to review the current existing customers.

Relevant thresholds

According to article 7 of the 3rd directive, a customer due diligence was required when establishing a new business relationship, when carrying out occasional transactions amounting to € 15,000 for single transactions or when several operations appear to be linked, where there is a suspicion of money laundering or terrorist financing or where currently existing customer information seems to be insufficient.

The new directive does not completely change those requirements; however it differentiates the transaction threshold. For transfers of funds according to article 3 (9) regulation (EU) 2015/847, the threshold is set to € 1,000, including credit transfers, direct debit transactions as well cross-border transactions “carried out using a payment card, an electronic money instrument, or a mobile phone, or any other digital or IT prepaid or postpaid device”. A threshold of € 10,000 applies for persons “trading in goods, when carrying out occasional transactions” in cash and finally the specific threshold of € 2,000 “applies for providers of gambling services, upon the collection of winnings, the wagering of a stake, or both”.

Excursus: The Swedish Solution

The Swedish act on anti-money laundering and terrorism financing (2009:62) is based on the 3rd directive and entered into force in 2009. The work on the implementation has taken longer and still imposes challenges to the obliged entities. This is shown e.g. by the recent fines handed by the Swedish FSA to two of the largest banking groups in Sweden[4].

The Swedish regulator shows an ambition of becoming “best in class” with regard to anti-money laundering measures. Given this ambition, together with the fact that Sweden is to be audited by the FATF in 2016, Sweden is already one step ahead of the requirements imposed by the 4th directive.

Hereby the updated recommendations from the FATF are the fundament on which the 4th directive relies upon, although the 4th directive is more ambitious than the standards in some respects. As Sweden has the ambition of becoming compliant with the FATF standard as quickly as possible, the regulator has already implemented some of the standards in advance in parallel with the EU work with the 4th directive.

The progression is running in two parallel tracks;

- The proposition of 2014/15:80 on the adoption of certain international standards (the FATF standards) to the anti-money laundering and terrorism financing act, and

- The committee directive of 2014:140, an investigation on how to implement the 4th directive in Swedish legislation.

The proposition came into force on the 1st of August 2015 and partially introduced some of the FATF standards from 2012, and hereby already parts of the 4th directive. The changed legislation implemented the risk-based approach and a requirement on a documented risk assessment. Furthermore, it implemented the specification of the definition of PEP and ensures that, other than in the past, Swedish people can also be PEP. A PEP can be a person with a leading position in an international organization as the UN or similar. The obliged entities are furthermore required to regard a PEP as a person that implicates high risk which has previously merely been a presumption.

Furthermore, Swedish legislators drafted a whole new chapter on data privacy and has introduced a requirement for the obliged entities to store specific information, e.g. on transactions for five years. Another new requirement is that obliged entities – when assessing situations that could have an effect on the risk exposure of the entity – should take into account the use of technique that is new for the company.

Those examples show that several aspects of the 4th directive have already been implemented in Swedish legislation. However, the committee directive of 2014:140 should have been presented in summer 2015, but has been postponed presumably until December 2015. Therefore, there are some significant question marks on how Sweden will proceed with the implementation of the 4th directive. As the 4th directive is a minimum directive, which means that a Member State can choose to have additional or stricter requirements, obliged entities should closely monitor the developments during fall 2015.

Implications

The 4th directive and the subsequent legal acts will have a high impact on the obliged entities. Obliged entities are recommended to check, if the current strategies, processes and procedures are appropriate to comply with the new requirements. Furthermore, obliged entities are required to develop a methodology to perform a risk assessment which captures all potential risk factors.

Obliged entities should define the methodology and responsibility for the risk assessment of risks they are exposed to, as well as the reliance of the identification of PEP within the customer due diligence. Additionally, the currently applied transaction thresholds will change and have an impact on the level of due diligence as well as the number of transactions to be checked. Furthermore, existing documentation requires revision as well the training of staff being in charge of the due diligence process.

International supervisors have recently set high fines for non-compliance with the AML regulations. Considering the fact that the risk assessment is one major element of designing due diligence, the monitoring and reporting which are in turn fundamental elements of a holistic AML framework and thus obliged entities are recommended to initiate a holistic review of their framework.