Complete vs. incomplete financial markets

“Complete” financial markets can be defined as those in which any possible future state of the world can be replicated/hedged with existing financial instruments with minimum friction. For example, central banks’ overnight interest rates can be hedged with reasonable accuracy through Fed Funds futures, overnight index swaps (OIS) or certain repo-based products (such as Switzerland’s SARON, a reference rate based on data from the Swiss franc repo market).

“Incomplete” financial markets, on the other hand, refer to situations in which market participants lack certain financial instruments to hedge against all undesirable outcomes. Causes for this may include: A lack of financial innovation has not (yet) led to the development of such instruments; required instruments are prohibited, over-regulated, taxed or otherwise impaired in their ability to serve as a hedge; fiscal and/or monetary policy has created financial exposures that cannot be (easily) replicated by financial markets.

Self-healing properties of competitive financial markets towards completeness

Highly competitive financial markets will always gravitate towards creating a complete market due to the fact that hedging needs and diverging competitive advantages create enough of an incentive to spark financial innovation that results in financial engineering of the “missing” products. Many of those are exchange-listed derivatives and over-the-counter (OTC) instruments. However, one necessary condition for this process to take place is that the to-be-hedged financial exposure affects market participants equally. If there is artificial market segregation into various groups of market participants that face different consequences in a particular future state of the world, a one-and-for-all financial hedge instrument cannot be developed.

Case study SNB: Monetary policy causing market segregation

On January 22, the Swiss central bank (SNB) lowered the deposit rate to -0,75%, an event that received much attention, not least because of interest rates being negative. Less so at the center of discussion is the fact that deposits up to 20-times the minimum deposit requirement are exempt from being charged with negative interest rates. This creates interest rate exposures highly dependent on the institution making SNB deposits. One group of market participants, into for example Credit Suisse is expected to fall, will not be charged negative interest rates at all because their current level of SNB deposits are below the threshold; others do not benefit from the negative-interest-rate exemption as their deposits exceed the threshold. SNB’s monetary policy rules have artificially segmented the market for short-term central bank deposits such that future states of central bank deposit rates cannot be hedged (due to the fact that each market participant faces a different mix between deposits that are exempt and those that are non-exempt from negative interest rates).

Hedge efficiency of existing financial instruments

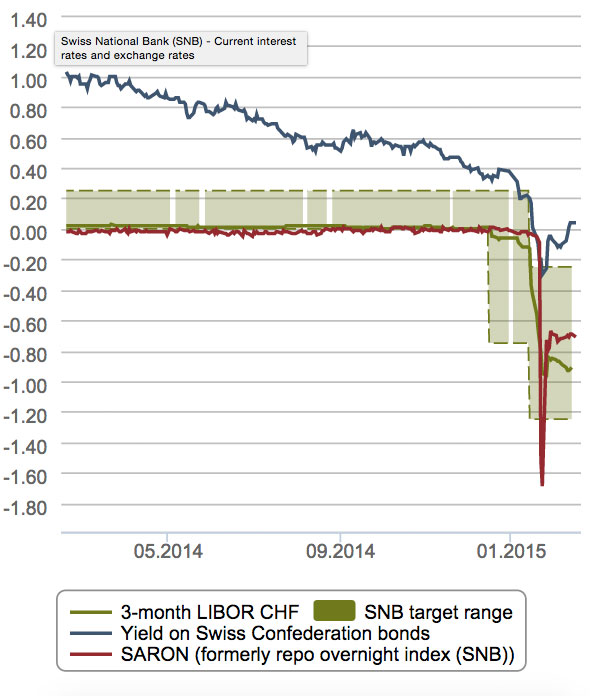

The increasing tracking error of existing financial instruments since the SNB’s bifurcated interest rate policy can be easily observed in Fig. 1. While central bank deposit rates were charged equally (above 0%) for all market participants, both 3-month LIBOR as well as the Swiss repo-based SARON rate were tracking the lower bound of the SNB’s target corridor. Now, those instruments closely track the non-exempt negative deposit rate of -0,75%. Institutions able to deposit at 0% with the SNB (because deposits are below the 20-times-of-the-minimum-deposit threshold) would face significant tracking errors when using LIBOR- or Repo-based instruments. The same is true, although to a lesser degree, for institutions benefiting from a partial exception from negative interest rates and, thus, facing a mixed deposit rate that is somewhere between 0% and -0,75%.

Resulting challenges for financial innovation

In principle, the market could be expected to develop new financial contracts that synthetically replicate newly created financial exposures. However, in case of the segregated central bank deposit market in Switzerland, this is far from trivial, if even possible. A market participant selling the exposure to the interest rate charged for deposits below the SNB reserve threshold (currently at 0%, but potentially subject to change) could only hedge himself by making SNB deposits below that threshold. Many market participants are not able to do so, however, and even those who are can only hedge up to a certain volume (from which on they would see their SNB deposits go over the threshold). Thus, this exposure cannot be efficiently hedged and a financial instrument based on it will likely not be developed. Even if proxy-hedges or partial hedges are to be engineered, their uncertainty and illiquidity will likely make them unsuited for end-users. In the end, the Swiss financial market will likely remain incomplete as far as the central bank deposit rate is concerned.

Temptation for other central banks and resulting risks

Having moved into a zero interest-rate policy (ZIRP) environment, many central banks around the world are tempted to implement creative, new policy actions beyond quantitative easing (QE). Such policies may include “tailor-made” interest rate offerings to particular sub-sets of all market participants. An example would be to allow certain investors or even consumers to borrow directly from the central bank at a (politically motivated) preferred rate. While such market interferences are often portrayed to be beneficial from a macroeconomic perspective (repairing monetary policy transmission channels, fighting deflation etc.), they also create new economic exposures that, by the very nature of how they are defined, cannot be easily hedged with financial instruments. The resulting costs of an incomplete financial market may then easily outweigh the expected benefits from the market intervention.